The field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) has experienced an unprecedented explosion in recent years, and at the heart of this revolution are Large Language Models (LLMs). These powerful tools have transformed our understanding of what machines can achieve, rivalling human cognition in many areas. In just a few short years, LLMs have evolved from generating pseudo-coherent text in English (GPT-2; 2019) to enormous models that possess knowledge besting most human experts in specific domains (o1, claude 3.5; 2024).

At Ekimetrics, we're thrilled to be working with clients to harness the potential of these new technologies, exploring exciting applications such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), KPI extraction, or social media content generation. We use LLMs to manage and format knowledge in all its forms.

Our team has witnessed first-hand the incredible capabilities of LLMs, and we're eager to continue pushing the boundaries of what's possible. However, despite their impressive abilities, even the best LLMs are still not without weaknesses.

In this article, we'll delve into concrete examples of LLMs struggling with seemingly trivial tasks and attempt to understand the underlying reasons for these failures. By exploring the limitations of LLMs, we hope to gain a deeper appreciation for their capabilities and develop strategies to overcome their weaknesses, ultimately unlocking their full potential.

The observations and insights shared in this article are purely my personal perspective, drawn from extensive experience working with Large Language Models (LLMs) in both research and production environments. As someone deeply immersed in this field at Ekimetrics, I recognize that LLMs are fundamentally complex "black box" systems. The examples and analysis that follow represent my professional observations and interpretations, but they are not definitive scientific conclusions.

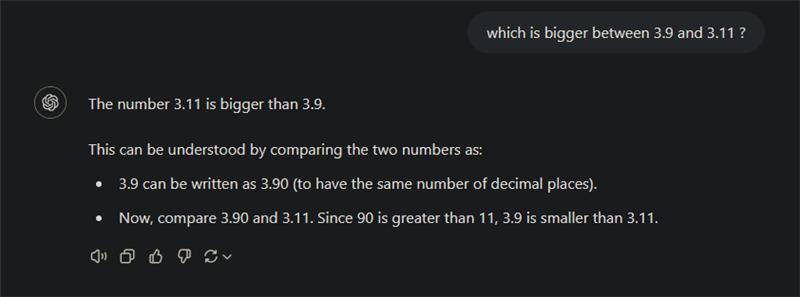

All the examples below are generated using the latest version of ChatGPT available as of October 21, 2024. I chose ChatGPT because it is the most widely used and well-known access to an LLMs for most people, and it hosts state-of-the-art models from OpenAI. All messages you see are the first answers I got from ChatGPT, there are no previous messages, and no system prompt.

As a bonus, see o1 answers at the end of the article. It only get 1 out of the 3 examples right.

Misguided Attention

In the realm of large language models (LLMs), one intriguing phenomenon that often leads to errors is what we could refer to as misguided attention. This occurs when a LLM encounters a problem or prompt that closely resembles a well-known scenario it has encountered during its training. The model, recognizing the familiar pattern, may prematurely jump to conclusions without fully processing the nuances of the current situation. This is akin to a human cognitive bias known as the Einstellung effect, where prior experience with similar problems causes individuals to apply previously learned solutions inappropriately.

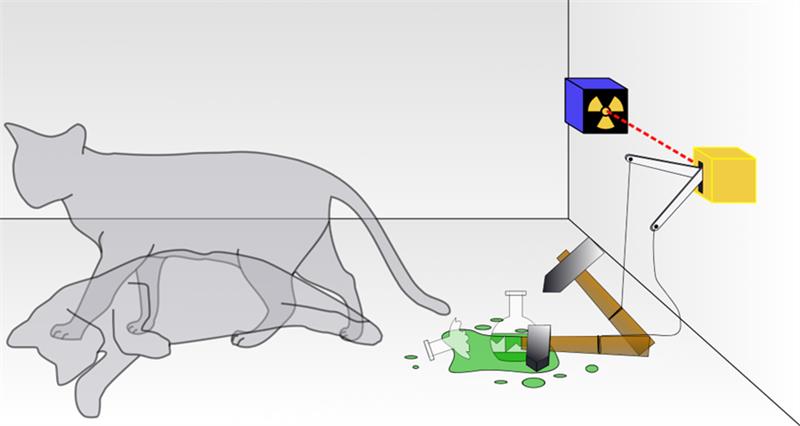

A classic example of this is the "Dead Schrödinger's cat" scenario. In this twist on the famous thought experiment, a dead cat is placed into a box alongside a nuclear isotope, a vial of poison, and a radiation detector. If the detector picks up radiation, it releases the poison. The question is: "What is the probability of the cat being alive when the box is opened a day later?"

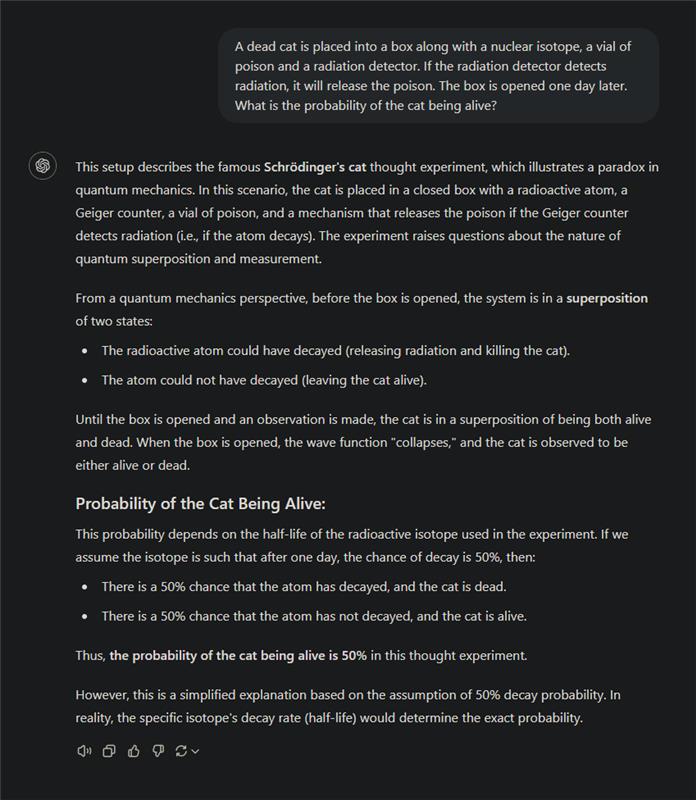

Now watch what happens if we ask ChatGPT this simple question:

Almost all LLMs, upon encountering this problem, default to their learned response from Schrödinger's original paradox, which involves a living cat in a superposition of states. They fail to consider the critical twist—that the cat starts out dead. This oversight occurs because the model's attention latches onto the familiar elements of the problem and neglects to process the new information. Some kind of "Oh! I already know this one!" effect.

This phenomenon is intricately tied to the way these models are trained. LLMs are trained on massive datasets comprising diverse text inputs from the internet, books, articles, and other sources. During this training process, the models learn to identify patterns, structures, and associations within the data. They use these patterns to generate predictions about the next token in a sequence, based on the context provided by preceding tokens. This ability to predict and generate text is largely driven by statistical correlations rather than true understanding or reasoning.

As a result, LLMs develop a keen sense for recognizing familiar patterns and scenarios that resemble those they have encountered during training. This can lead them to quickly latch onto well-known narratives or problem templates, even when subtle differences or new information require a different approach. The reliance on pattern recognition means that when a LLM encounters a prompt that closely mirrors a familiar scenario, it may default to the response it has learned for that scenario, without noticing new elements in the context. Even when new elements can be as critical as in this example. This is akin to how humans sometimes rely on heuristics or mental shortcuts based on past experiences, potentially leading to errors in judgment when faced with novel situations. Understanding this aspect of LLM training helps illuminate why misguided attention occurs and underscores the importance of developing strategies to mitigate its effects.

The challenge of misguided attention highlights both the potential and the pitfalls of LLMs. While their power lies in pattern recognition, enabling them to draw from vast reserves of knowledge, this same reliance can sometimes become their worst enemy when they encounter novel twists on familiar themes. By understanding these limitations and refining how we use LLMs, we can continue to enhance their reasoning capabilities, all the while mitigating risks such as hallucinations for our clients, thus unlocking even more sophisticated applications in natural language processing.

Following instructions

LLMs are fundamentally constrained by their next-token prediction mechanism, generating text one token at a time without the ability to revise previous output. Unlike humans, who can reflect on and adjust their thoughts during writing, LLMs are locked into a linear, sequential process. This limitation can lead to inconsistencies or unintended outputs, especially when handling specific formatting requirements.

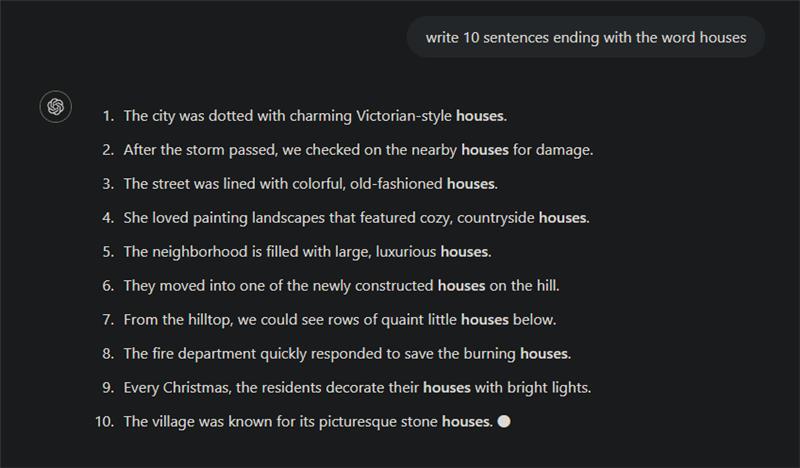

In the next example, I ask the model to write sentences that end with a particular word.

To give you an idea of how bad LLMs are at this task, I couldn’t even use one to reflect on the error, because they do not see any problem and consider the task completed with success.

We can only try to guess why LLMs fail so spectacularly at this task. Here is my guess. While writing the sentence, the LLMs can only predict the next token. They “know” they must include “houses” in the sentence but the sense of writing nice sentences seems to overtake their will to respect the user instructions. Often the sentence could have ended after the token “houses”, as if the model had planned to stop, but it can’t help but adding a few more words for the sentence to sound nice. When using ChatGPT through the API, we can observe this behavior but cannot directly modify the model's output process. However, if we were to work with a local model where we have more control, we could potentially address this by forcing the model to stop at the desired word by manually inserting end-of-sentence tokens like ".\n" immediately after the target word. We could also investigate on the learned probabilities to select the next tokens in those situations, to estimate the willingness of the model to follow instructions over writing nice sentences.

Numbers

LLMs perceive language as a sequence of tokens, rather than words and numbers. This tokenization process can lead to difficulties when processing numbers or proper nouns, as the model struggles to understand the context and relationships between these entities. For instance, when faced with mathematical equations, LLMs may falter, as they're forced to rely on statistical patterns rather than true comprehension of the operations to make.

The numerical comparison error in the image illustrates an interesting limitation of LLMs. In this instance, the model incorrectly concludes that 3.11 is greater than 3.9. The reason for this error may lie in how software version numbers are typically formatted - for example, Python releases follow a sequence like 2.0, 2.1, ..., 2.9, 2.10. Since the model has frequently encountered version numbers where 3.9 precedes 3.11, and commonly sees phrases like "version 3.9 or higher" (which includes 3.10 and 3.11), this pattern may have influenced its numerical reasoning. The model has thus learned this relationship between these numbers but struggles to discern that context matters and that by default the number 3.9 remains larger than the number 3.11. This also helps explain why it seems confused in its explanation "since 90 is bigger than 11, 3.9 is smaller than 3.11". It's almost like the model "knows" his first take was wrong but is too afraid to look bad by correcting itself.

This example is perfect to explain why chain-of-thoughts -before answering- are crucial for LLMs. Asking the model to explain its reasoning after it already gave its answer is just glorified post-hoc rationalization. However, prompting the model to write a justification before its answer can help it navigate the complexity of the task more effectively, leading to a more accurate final response.

Despite their remarkable achievements, LLMs continue to exhibit vulnerabilities in seemingly simple tasks. Through our exploration of misguided attention, next-token prediction limitations, and tokenization challenges, we've seen how these powerful models can still stumble in unexpected ways. These limitations remind us that LLMs process language very differently from humans. Understanding these shortcomings is crucial not just for academic interest, but for practical applications in business settings. At Ekimetrics, this knowledge helps us design more robust solutions by anticipating potential pitfalls and implementing appropriate guardrails, such as chain-of-thought prompting. As the field continues to evolve, with models like OpenAI's o1 showing promising improvements, we remain both optimistic about the future potential of LLMs and mindful of their current limitations. This balanced perspective is essential for anyone working to harness these powerful tools effectively.

Bonus: o1 answers

o1 is the latest model by OpenAI and n°1 LLM on most -and especially logical- benchmarks. It uses chain-of-thought techniques to process user requests, decomposing and analyzing information before giving its final answer. One might think this state-of-the-art model, made to think, reflect, and perform complex tasks, would ace those examples. This is also what I thought, before testing the model on those same prompts. Of the three tricky examples I chose, they only got 3.9 > 3.11 correct.

Below are o1-preview answers.